The Gospel of Matthew presents the Sermon of the Mount as the fulfillment of the Torah: just as Moses went up Mount Sinai to receive the Torah, so Jesus goes “up the Mount” to give to the people the new Torah.

The Gospel of Matthew presents the Sermon of the Mount as the fulfillment of the Torah: just as Moses went up Mount Sinai to receive the Torah, so Jesus goes “up the Mount” to give to the people the new Torah.

- «You heard that it was said by our ancestors ‘Do not kill’, and those who have killed will undergo judgment. But I say to you: anyone who gets angry with his own brother will undergo judgment...»

- «You have heard that it was said 'do not commit adultery'. But I say to you: Anyone who looks at a woman to desire her, has already committed adultery with her in his heart...»

- «It was also said ‘ he who repudiates his wife shall give her the writ of dismissal’. But I say to you: whoever repudiates his wife...exposes her to adultery and he who marries a repudiated woman commits adultery...

- «You have also heard that it was said to our ancestors: ‘do not swear in vain’... But I say to you: do not swear at all...»

- «You have heard that it was said: ‘eye for eye and tooth for tooth’. But I say to you do not resist evil; but instead, if one strikes you on one cheek, offer him the other...»

- «You have heard that it was said ‘you shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy’. But I say to you: love your enemies, pray for your persecutors, so that you may be children of your Father in heaven, that makes the sun rise over the evil and good alike and makes the rain fall over the just and unjust.

No other text sounds so radically new after 2000 years. Contrary to the most diffused perception, the heart of the sermon is not the beatitudes; but rather this new Decalogue in six articles which. Jesus proclaims advocating for himself the authority of God and and placing it explicitly in contraposition to the old Decalogue (‘You have heard how it was said...but I say to you’). The sermon of the mount passes in front of the Decalogue. The new torah culminates in the invitation to love the enemies which is the heart of all the teachings of Jesus.

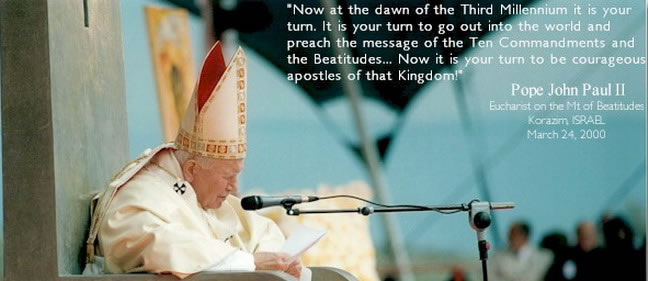

John Paul II, in 1987, said:

«And here is the definitive perfection, in which all the others find the dynamic center: ‘You have understood that it was said: You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy; but I say to you: love your enemies...' To the vulgar interpretation of the ancient Law which identified the neighbor with the Israelite or rather with the pious Israelite, Jesus opposes the authentic interpretation of the commandment of God and adds the religious dimension of the reference to the Father in heaven who is clement and merciful, who benefits all and is therefore the supreme example of the universal love. Jesus in fact concludes: “Be...perfect as your Father in heaven is perfect” (Mt.5,48). He asks of his followers perfection of love. The new law he brought has love as its synthesis. This love will enable man to overcome ,in his relationships with others, the classic friend-enemy contraposition. It will have the tendency, from within hearts, to translate itself into corresponding forms of social and political solidarity, also institutionalized. It has been therefore ample, in history, the irradiation of the “new commandment” of Jesus.»[1]

All cultures base themselves on this friend-enemy contraposition. The one who is different because of race, behavior, language, clan, tribe, nation, who today could be the Jew, tomorrow the Kulakh, the homosexual, the gypsy, is always seen as the enemy to be kept at a distance or killed. The Gospel announces the destruction of this fundamental structure of human relationships. Therefore Western history and culture have been marked profoundly by this Gospel: behind every initiative in favor of the oppressed, of those who are excluded, of the minorities, behind every position taken against torture, racial segregation, slavery, this word is always found: love your enemies.

All cultures base themselves on this friend-enemy contraposition. The one who is different because of race, behavior, language, clan, tribe, nation, who today could be the Jew, tomorrow the Kulakh, the homosexual, the gypsy, is always seen as the enemy to be kept at a distance or killed. The Gospel announces the destruction of this fundamental structure of human relationships. Therefore Western history and culture have been marked profoundly by this Gospel: behind every initiative in favor of the oppressed, of those who are excluded, of the minorities, behind every position taken against torture, racial segregation, slavery, this word is always found: love your enemies.

Nietzsche , prophet of today’s postmodern nihilism, clearly underlined that at the root of any idea of compassion and pity towards the poorest and the different ones, we find the words of the Gospel. These are the hidden base of every idea for living in common and for universal tolerance. These ideas would be unthinkable in cultures not leavened by the Sermon of the Mount. If we erase it, man will return to the dionisiac barbarities of human sacrifice. The twentieth century has seen the greatest attempt in the west to erase Christianity. It has also seen the greatest atrocities, where there is only room for the strongest, for those of my country, of my race, or of my party.

Jesus presents a new way of living and of resolving conflicts: no more revenge, nor judgment, but mercy in place of judgment. The pope, speaking in Ireland in 1983, considered the Anglo-Irish conflict in this prospective:

![]() «I ask you to reflect deeply: what would human life be like if Jesus had never pronounced these words (love your enemies...)? What would the world be like if in our sharing relationships we would give primacy to hate amongst individuals, among classes, among nations? What would the future of humanity be like if we had to base ourselves on this hatred, the future of individuals, or of the nation? Sometimes we could have the impression that, in front of the experiences of history and of concrete situations,love has lost its strength and it is impossible to practice it.Instead, in the long run,love alwaysbrings about victory, love is never failing. If it was not so, humanity would be condemned to destruction.[2]

«I ask you to reflect deeply: what would human life be like if Jesus had never pronounced these words (love your enemies...)? What would the world be like if in our sharing relationships we would give primacy to hate amongst individuals, among classes, among nations? What would the future of humanity be like if we had to base ourselves on this hatred, the future of individuals, or of the nation? Sometimes we could have the impression that, in front of the experiences of history and of concrete situations,love has lost its strength and it is impossible to practice it.Instead, in the long run,love alwaysbrings about victory, love is never failing. If it was not so, humanity would be condemned to destruction.[2]

Without this root, human society risks constantly to dissolve into reciprocal violence – even more clearly today in a time of nuclear war – and the only way to save it, is the possibility opened by Jesus to love the enemy. Speaking in 1979 at the polish cemetery of Monte Cassino, John Paul II affirms that the experience of two World Wars has taught something profound to mankind:

«The Gospel of today contra poses two programs. One based on the principle of hatred, revenge and of fighting, another on the law of love. Christ says: “Love your enemies and pray for your persecutors” (Mt. 5,44).... But, after such terrible experiences as the last war, we become even more aware that on the principle which says: “eye for eye and tooth for tooth” (Mt. 5,38) and on the principle of hatred, revenge, fighting, peace and reconciliation cannot be built among men and among Nations.»[3]

In every generation the Servant of Yahweh, the meek lamb who lets himself be killed without answering evil for evil and violence with violence, saves humanity and stops the wave of evil which otherwise tends to grow ever more until it crushes the weakest.

According to John Paul II, this vision, which some retain to be utopian and unreal, is instead the only realistic option. Utopian is rather the pretense to resolve conflicts based on a mere human justice. It is not a matter of a blind and passive pacifism or of a utopian program. The Church falls into utopianism, exactly when it tries to resolve social and political conflicts with human doctrines:

«It would be mere utopia not to take into account the Gospel, for those who want to heal at the root these and other matters which touch man directly at the heart. Only in the evangelical ideal of heroic charity, which Christ dared to propose to his followers, resides the secret of the victory over these passions, which poison the spirits: “But I say to you: love your enemies, do good to those who hate you...»[4]

To reject the Gospel is utopian, because it means to ignore that evil is born in the heart of every man. The problem of man is that, because of the fear of death, he is condemned to live for himself. Sin, while living in him, forces him to offers everything to himself: sexuality, money, family, culture, friends etc. His ‘I’, his ‘ego’ is the center of the universe. We all have a problem: we cannot give ourselves, donate ourselves; it costs us a lot to sacrifice ourselves, to suffer. For this reason, man is condemned to offer everything to himself: he is selfish.

With Jesus a new humanity appears. Christ has conquered death and is risen.

«Because the love of Christ urges us at the thought that if one has died for all, all have died. And he died for all, so that all who live may live no longer for themselves, but for him who died and is risen for them.»[5]

What does it mean that all have died? That Christ has given his life so that all men may be freed from death, from the power that death has over them. Christ has come to free us from this existential condition, making us new creations, born from above, so that in Him we can love the enemy, we can forgive, we can give our life, we can be open to life, we can enter into suffering. Man, through Christ, is placed in front of two possibilities: the total donation of oneself to the brethren or the total enclosure into selfishness.

«Christ knows well the difficulties men experience to reconcile themselves among each other. Through his sacrifice, the Redeemer has obtained for all the strength necessary to overcome them... The Cross has made fall all the barriers which close the hearts of men towards each other. In the world, there can be sensed an immense need for reconciliation. Fights involve at times all fields of the individual, familiar, social, national and international life. If Christ had not suffered to establish the unity of the human community, one could think that such conflicts would be unremedied...»[6]

Christ, then, asks the believer to love even those hostile to him and those who hurt him: «Love your enemies and pray for your persecutors» (Mt. 5,44). «But how could Man put into practice such a demanding invitation, if God did not touch his heart?»[7] Faith, that is, the meeting with the risen Christ, precedes charity and is its cause. For this martyrdom is the most significant act of the Christian. Jesus, after having given this paradigmatic catechism, this Carta Magna of Christianity, this picture of the new man born from above, sends the disciples to all the nations.

Christ, then, asks the believer to love even those hostile to him and those who hurt him: «Love your enemies and pray for your persecutors» (Mt. 5,44). «But how could Man put into practice such a demanding invitation, if God did not touch his heart?»[7] Faith, that is, the meeting with the risen Christ, precedes charity and is its cause. For this martyrdom is the most significant act of the Christian. Jesus, after having given this paradigmatic catechism, this Carta Magna of Christianity, this picture of the new man born from above, sends the disciples to all the nations.

On this Mount after 2000 years since Jesus sent his disciples to all nations, for the first time in history Peter reunites with thousands of youth from all over the world. This means that the mandate the disciples received is fulfilled: these youths are the witnesses that this word has been fulfilled. But this event has also another much more profound meaning: to see this Mount full of youth from all over the world accompanying Peter at the beginning of the new millennium, has a prophetic meaning for all future generations.

«It is a matter now to look at the future, and this belongs to you, to the youth. It is necessary for you to undertake the great highways of history, not only here in

Europe, but in all the continents; and that you may become witnesses of the beatitudes of Christ everywhere: “Blessed are the peacemakers because they will be called Sons of God" (Mt.5,9)»[8]

Today we find ourselves in an era that would like to erase these words. For this reason the Pope said:

«The future of all the peoples and Nations, the future of humanity itself depends on this: whether the words of Jesus in the Sermon of the Mount, whether the message of the Gospel will be listened to once more.»[9]

References

[1] John Paul II, General Audience, 14 October 1987.

[2] John Paul II, Homily at Galway, Ireland, 30 September 1979.

[3] John Paul II, Homily at the Polish cemetery of Monte Cassino May 17, 1979.

[4] John Paul II, Audience with pilgrim groups, 3 March 1984.

[5] 2 Cor 5,14-15

[6] John Paul II, General Audience, 18 May 1983.

[7] John Paul II, Mass at the Airport – Szombathely, August 1991.

[8] John Paul II, Arrival at the Sanctuary of Jasna Gora- Hungary, 14 August 1991.

[9] John Paul II, Homily in Galway, Ireland, 30 September 1979.